Some time ago, I watched three films: “American Fiction,” “Io Capitano (Italian for I am the captain),” and “Hidden Figures.” I kept putting off writing about them, but one afternoon, scattered thoughts in my mind felt like they were being threaded together with strands of gold and silver, forming circles of rhythm.

Let’s start with “Io Capitano”:

Sixteen-year-old Seydou from Senegal dreams of showcasing his musical talents in Europe, envisioning a future where “white people line up for his autograph.” Determined to make this a reality, he secretly plans with his cousin Moussa to save money and leave home, hoping to illegally travel from Senegal through Libya to Italy.

Their journey takes them across the Sahara Desert and toward the Mediterranean. Along the way, they are scammed while trying to obtain fake passports, witness exhausted women abandoned under the scorching sun, and watch helplessly as fellow travelers are thrown from trucks and left to fend for themselves in the desert. The barren landscape shows no mercy to every drop of water – even the last tears shed evaporate into nothingness.

The starry night sky over the desert is like a flowing paradise. But for Seydou and his companions, it brings darkness—armed militants rob them of everything and kidnap them, subjecting them to inhumane abuse in prison. Carpenters and masons are sold off as forced labor. Seydou, however, meets a kind older man, and together they work building fountains for the wealthy. Thanks to their hard work, they are eventually released. In Tripoli, Seydou reunites with his long-lost cousin, Moussa, who was shot in the leg while trying to escape. His wound worsens, leaving him with no choice but to seek treatment in Italy.

Seydou is deceived once again by smugglers and boards a rickety, overcrowded boat to cross the strait. Moonlight shimmers over the Mediterranean, but hardships quickly follow. The journey becomes increasingly brutal with fierce winds and waves, the spread of illness, the suffocating cramped space, and a passenger going into labor—all compounding the ordeal at sea.

Seydou is deceived once again by smugglers and boards a rickety, overcrowded boat to cross the strait. Moonlight shimmers over the Mediterranean, but hardships quickly follow. The journey becomes increasingly brutal with fierce winds and waves, the spread of illness, the suffocating cramped space, and a passenger going into labor—all compounding the ordeal at sea.

As the boat nears Sicily, the cramped cabin erupts with cheers as everyone embraces in celebration. Standing at the bow, Seydou shouts with joy, “I am the captain! I did it! I saved everyone—no one died! I am the captain! I am the captain!”

As the boat nears Sicily, the cramped cabin erupts with cheers as everyone embraces in celebration. Standing at the bow, Seydou shouts with joy, “I am the captain! I did it! I saved everyone—no one died! I am the captain! I am the captain!”

The film ends with an extended close-up of Seydou. At times, he mumbles softly; at others, he stays silent, his cracked lips slightly parted. Positioned to the right of the frame, his gaze remains fixed toward the front left. The shot leaves unanswered what he sees—it could be the bright, vibrant Sicily he longed for, the music of his dreams, or perhaps an even harsher reality. Every fairy tale, even a dark one, must eventually reach the shore.

Fast-forward to years later: if these immigrants from distant lands thrive across Europe and America, receive quality education, and become part of prestigious institutions, we step into the world of “Hidden Figures”.

This film, based on true events, portrays the United States during the era of racial segregation, where Black people were marginalized at the bottom of society, enduring both systemic racism and oppression while also facing the constant threats of unemployment, poverty, and death. Against this backdrop, the movie tells the story of three Black female mathematicians at NASA who made significant contributions to the American space program. Despite facing both gender and racial discrimination, they gradually overcame these barriers through their talent and hard work, ultimately earning the respect they deserved.

This film, based on true events, portrays the United States during the era of racial segregation, where Black people were marginalized at the bottom of society, enduring both systemic racism and oppression while also facing the constant threats of unemployment, poverty, and death. Against this backdrop, the movie tells the story of three Black female mathematicians at NASA who made significant contributions to the American space program. Despite facing both gender and racial discrimination, they gradually overcame these barriers through their talent and hard work, ultimately earning the respect they deserved.

The film portrays discrimination and prejudice with the force of a heavy hammer—direct and impactful—yet the expression is subtle like soft cinnabar slowly seeping through a hydraulic press.

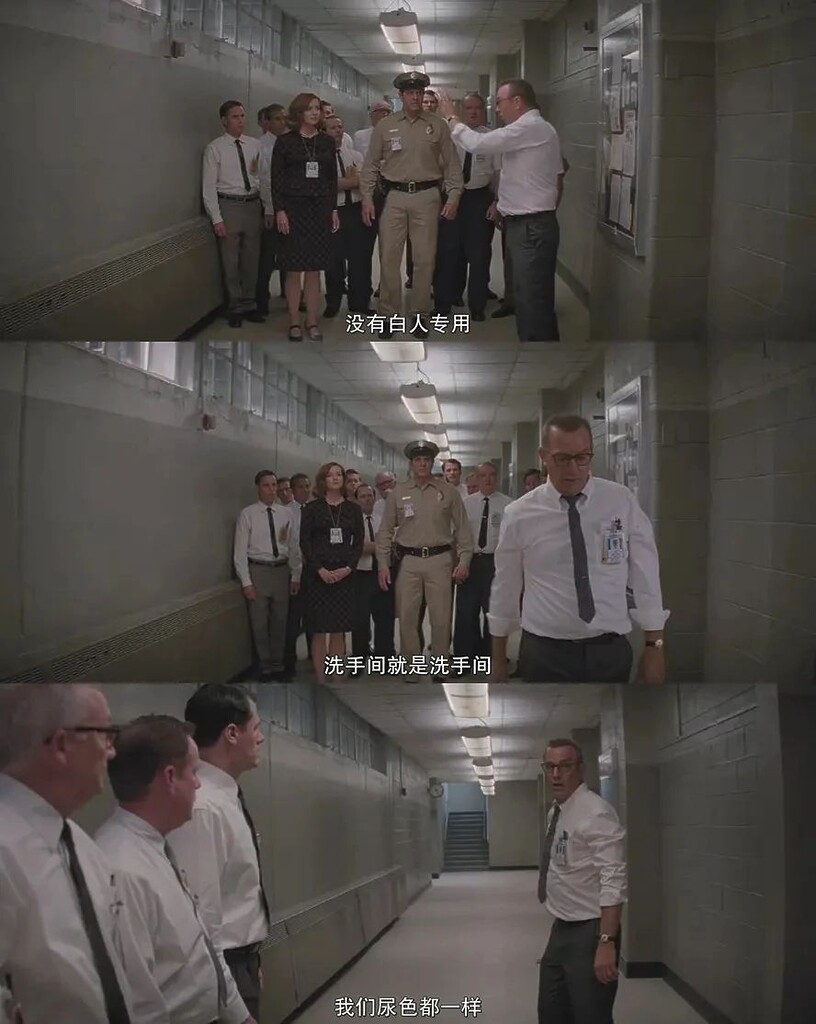

Discrimination isn’t just treating others unequally based on flaws, abilities, or background. It’s reflected in Katherine being mistaken for a janitor and told to take out the trash on her first day in the office. It’s the stares she endures simply for sharing a room with her male colleagues. It’s the lack of a seat for her on the bus. It’s the 20-minute journey she has to make to another building to use a restroom designated for “colored women.” And it’s the communal coffee pot that nobody touches again after she uses it.

White and people of color are artificially segregated, resulting in resentment and oppression. In the face of this oppression, the three female protagonists demonstrate a resolute and tenacious spirit. The film adopts a direct approach to countering oppression, avoiding overly dramatic embellishments or emotional manipulation. Instead, it reveals the power that bursts forth from long-accumulated daily struggles.

When Katherine’s boss reprimands her for taking too long in the restroom, a pivotal emotional scene unfolds in the office. Standing in front of her colleagues, she asserts, “There’s no bathroom for me here. There are no colored bathrooms in this building, or anywhere near, and I have to walk to Timbuktu just to relieve myself. And I can’t use one of the handy bikes. Picture that, Mr. Harrison: my uniform, skirt below my knees, heels, and a simple string of pearls. Well, I don’t own pearls. Lord knows you don’t pay coloreds enough to afford pearls! And I work like a dog, day and night, living off a pot of coffee that none of you want to touch!”

After Dorothy is ejected from the library for trying to purchase books, she calmly tells her children on the bus, “Just because it’s the way, doesn’t make it right.”

Mary faces continuous obstacles in her quest to become an engineer due to her skin color, ultimately choosing to confront the judge in court.

In the end, through their sincerity, hard work, and exceptional talents in their respective fields, Katherine’s boss removes the sign designating the restroom for “colored women.” A male colleague, who previously held biases against her, brings her a cup of coffee, while a female colleague gifts her a pearl necklace. There’s no hysterical tragedy or accusation; the resolution is handled with exceptional warmth. Reclaiming their dignity and worth through their own abilities is particularly powerful.

The winds are continuously shifting for the better. From “Moonlight” to “Green Book,” Black cinema has captured global attention. In recent years, Asian films like “Parasite” and “Everything Everywhere All at Once” have flourished, alongside a focus on disabled individuals in *”CODA.”* Minorities are receiving recognition and acclaim at the Oscars, with multiculturalism and diverse skin tones becoming synonymous with “political correctness.” It feels as though we have entered the “best of times,” leading us to “American Fiction.”

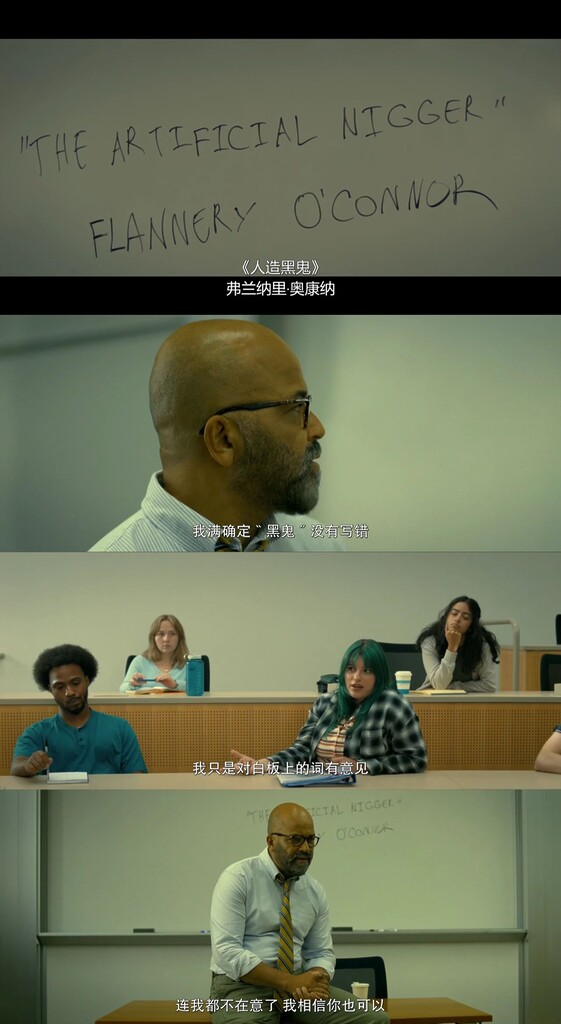

This film, directed by a white filmmaker, received five Oscar nominations and ultimately won for Best Adapted Screenplay. The protagonist, Monk, is a university professor and writer, enjoying a respectable profession and a life above middle-class standards. At the film’s outset, he candidly discusses Black literature in class, inadvertently using a term that offends a Black character, which ultimately leaves a white female student feeling hurt. As a result, he is forced to take a leave of absence.

On one hand, his works are lofty and obscure, lacking any distinctive Black characteristics. He hopes to break down racial boundaries and stereotypes through his writing, but as a result, his book launch is attended by only a handful of people, and the book fails to attract any interest in the market.

On the other hand, he observes another highly educated Black woman whose writing focuses on the struggles of the Black underclass to cater to the white market. She delivers clichéd remarks on stage, and the audience erupts in applause, finding her work immensely popular.

He knows that to capture attention, he needs to write about the tragic experiences of the Black community—stories like “police killings of young people” or “a single mother raising five children in a poor neighborhood”—but he cannot compromise his own principles.

Feeling dissatisfied at work and faced with the unpredictability of life, he experiences a series of personal tragedies: his sister’s unexpected death, his mother’s diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, and his brother’s long-term drug addiction. Amidst financial struggles and mounting resentment, he adopts a stereotypical Black name and writes a book that conforms entirely to the clichés of Black identity—one he considers devoid of literary value. Ironically, this book catches the eye of a prominent publisher and producer who is willing to pay a high price for the rights and even expresses interest in turning it into a film.

At this point in the story, it elegantly and ironically straddles the line between absurdism and family drama. Unlike the previous two films, which are supported by strong narratives and powerful core values, this film possesses a refreshing artistic quality in its use of empty frames, reminiscent of sharp cynics subtly revealing their wounded romanticism.

In the second half of the story, Monk fabricates a false identity as a wanted criminal, and the white audience reacts with even greater enthusiasm, exclaiming that a book written by a Black fugitive is “so cool, this is real!” In a moment of impulsiveness, Monk unexpectedly changes the book’s title to *”F**K,”* thinking that the publisher will back out. To his surprise, this outrageous title not only boosts sales but also earns a nomination for a literary award for which Monk himself serves as a judge. Following a public vote, the book ultimately wins the award for Best Work of the Year.

In the end, as a screenwriter, Monk does not provide a definitive conclusion. “Perhaps, as a serious writer, he, too, is uncertain about how to wrap up this absurd drama.”

There are many excellent works that express themes of race and skin color in diverse ways. These three films, each with their own stories and historical contexts, may not serve as direct reflections of reality. However, I watched them one after another, and since their subjects all revolve around the Black community, it makes sense to connect them together.

At this stage, we see Black teachers standing in classrooms, teaching students. During my recent study abroad experience, I felt the richness of multiculturalism while riding the subway or bus, as well as in the classroom. The students sitting below me had different skin tones, and each teacher spoke with a unique English accent. Life in reality seems to offer a sense of openness and diversity. Yet, when returning to “American Fiction,” the film astutely and sensitively expresses another form of dilemma beneath this diversity—the damage that stereotypes inflict on art. The stories are small yet beautiful, sharp as a knife.

Consciousness has evolved, and there are always those who understand the need for a pure land. Skin color may not change, but names need to shine.

He is not the captain; he is Seydou.

They are not hidden figures; they are Katherine, Dorothy, and Mary.

He is not Leigh; he is Monk.