Subtraction

Zhang Sanjian is back on March 13, 2024 at 06:30

Recently, during a meeting at work, I recommended my colleagues to watch a movie. Unexpectedly, when I mentioned the name, they said, “See? I said a few days ago that the boss would probably recommend this movie.”

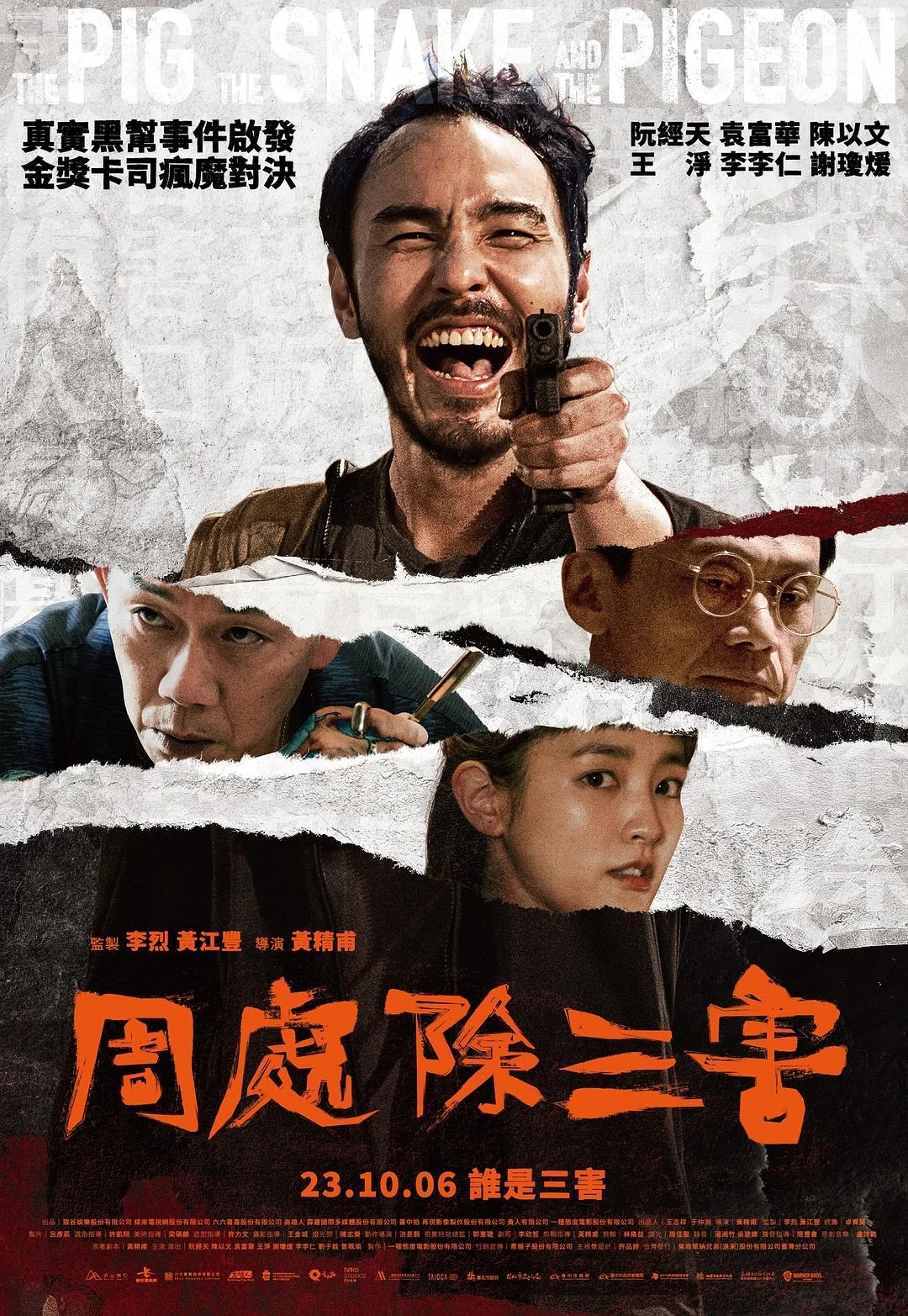

That’s right. It’s the movie “The Pig, The Snake And The Pigeon .” The title of the movie comes from a well-known anecdote. It’s about a young man named Zhou Chu who, in his youth, used his exceptional strength to bully and oppress the villagers, earning the disdain of everyone. He was known as one of the “Three Evils,” along with the fierce tiger of the South Mountain and the wicked dragon under the Long Bridge. Later, Zhou Chu turned over a new leaf, repented of his wrongdoing, and single-handedly slew the fierce tiger and evil dragon, hence the phrase “eliminating the Three Evils.”

The film tells the story of Chen Guilin, a wanted criminal who learns that his life is nearing its end. He decides to surrender to the police but is surprised to find himself ranked only third on the most-wanted list. Determined to seek justice, he sets out to eliminate the top two criminals.

The film tells the story of Chen Guilin, a wanted criminal who learns that his life is nearing its end. He decides to surrender to the police but is surprised to find himself ranked only third on the most-wanted list. Determined to seek justice, he sets out to eliminate the top two criminals.This is a movie where the process may not be correct, but the outcome is somewhat acceptable. Nevertheless, in the present context, resorting to violence is never advisable. Although it may resonate with people’s basic emotions, it does not align with the rules of modern society. In the film, the weakening of the representation of justice by the police makes the protagonist, who represents evil, become the executor of justice.

Let’s talk about the “Three Evils.” The second on the wanted list, “Hong Kong Boy,” is a man covered in blood and notorious for his violent and ruthless behavior, causing terror among those around him. The top-ranked Lin Luhe, on the other hand, presents himself as gentle and kind. He uses his charm to brainwash the public, preaching benevolence while concealing his sinister intentions. The contrast between these two antagonists is like “black” and “white.”

But black is not absolute, and white is not always as it seems. Take Lin Luhe for example. He was once deeply involved in crime, committing over fifty shooting incidents and killing six policemen. Now, he presents himself as the venerable leader of the cult “New Spiritual Shelter.” Using rhetoric about purifying oneself of impurities through “vomiting black water from the abdomen,” he deceives his followers for money. Under the guise of purity, he preaches about the root of suffering being greed, anger, and ignorance. This portrayal almost reaches the peak of madness.

When Chen Guilin exposes Lin Luhe’s deception, he returns to the spiritual center and kills him. However, even after their leader’s death, the cult persists. The women who sang alongside him quickly takes his place, continuing to indoctrinate the followers with their songs.

Upon returning to the spiritual center, Chen Guilin gives the followers two options: leave within one minute or be killed. Some hurriedly escape, but many choose to stay, calmly awaiting their fate. Here arises my first point of doubt: should those who escape or those who stay be the ones to be shot?

In Chen Guilin’s eyes, those who choose to stay despite knowing the truth and willingly submit to brainwashing are guilty. Therefore, he shows no mercy and shots them one by one.

But what about those who leave? In that minute, apart from those who have not been brainwashed, there are Lin Luhe’s henchmen, who were responsible for carrying out the deception and harming ordinary people. Although their leader is dead, given time, they can easily choose a new leader and continue to con the public.

Who deserves to die more, the foolish or the deceivers?

These are villains without a tragic hue. Sometimes, to add depth to antagonist characters, many films embellish their stories with tragic experiences, suggesting that external factors forced them onto the wrong path. But this film largely downplays or conceals these experiences, yet the antagonist characters do not become one-dimensional. The male protagonist, Chen Guilin, is arrogant, crazy, and violent, with a strong desire for fame. But he still has a soft side, caring for his grandmother and showing compassion for the weak and children, even displaying some innocence.

After eliminating the top two evils and redeeming himself, another question arises: should a bad person who does a good deed before death be forgiven? There is a saying, “lay down the butcher’s knife and become a Buddha.” This movie provides a reasonable answer. As a person with a long list of crimes, he needs to face legal judgment. Chen Guilin demonstrates goodness amid evil, but this goodness is not enough to evoke sympathy from the audience when he is executed.

At the end, a foreshadowed twist is revealed (the news of his terminal illness was false). He shaves his beard, has his last meal, and smokes his last cigarette, calmly walking towards his end.

This brings me to my second point.

When Hong Kong Boy is subdued by Chen Guilin, his final words are, “Why? Give me a reason.” But Chen Guilin does not answer; a single cold shot ends his life, without any unnecessary actions or words. However, in handling the movie’s ending , just when the audience is engrossed in the intensified emotions, the film continues to lay out more plot details and show every minute aspect, diminishing its significance. Like a cup of fine wine diluted over time with too many ice cubes.

I remember a teacher once said that if something can be expressed through performance, then try to minimize dialogue. At the end, the actor playing the character with lung cancer appears with a shaved head, every gesture and expression bearing the weight of her illness. She tells Chen Guilin in prison, “The X-rays are not yours; those lungs are mine.” This line is followed by a close-up of the actor’s eyes, revealing the story’s dramatic reversal and character’s inner turmoil. The subsequent dialogue feels like spilled water from a cup.

Another point is when Chen Guilin shaves his beard. The film spends a considerable amount of time describing how the razor is smuggled into prison and why it must be brought in, feeling somewhat redundant in pacing. However, as the scene continues, the subtle performance of the actor helps me understand the necessity of the razor.

As Chen Guilin shaves, tears roll down his face. Looking at his clean-shaven self, resembling his former innocent life, he puts on a suit, symbolizing the end at this moment, as if his soul is waiting for redemption and rebirth. (This is my personal opinion: Would it be more impactful to leave the ending at this moment rather than meticulously capturing the entire process till everything lays on a white sheet?)

Sometimes, it’s quite necessary to employ the “less is more” approach. Being honest within the frame, expressing oneself sincerely, and leaving room for imagination outside the frame for the audience. I now prefer the right amount of blank space. Thinking back to a few days ago when a colleague was discussing copywriting with me, he wrote a lengthy passage and explained the meaning in detail. I politely said it was good and asked him to delete those paragraphs. He didn’t understand, “Why delete them? What if people don’t understand?” I said, “We often fear that the audience won’t understand and are reluctant to cut back. But in fact, the audience is very smart. The charm and impact of words lie in how much space for imagination beyond the words. I believe everything I want to convey is already in the work.”