Time is Like Aged Wine

Zhang Shanjian is back March 25, 2025, 06:49

The first time I watched Titanic was in elementary school, huddled on the sofa with my parents late at night, the TV flickering before us. Midway through, a pair of large hands covered my eyes a few times. Back then, swept up in the atmosphere, I took it for granted that this was a love story, and I thought I’d witnessed a moving romance—though I had no idea what love really was.

Years later, I sat down again for this 3-hour-and-47-minute film. The hands of childhood had been cast aside by a mind that fancied itself mature, facing a story whose ending I knew by heart. This time, my gaze turned more inward than outward, reflecting on myself rather than imagining others. Yet, what struck me anew was watching the narrative unfold—its details like piloting a submarine through the ocean depths. Sometimes you uncover a fishbone, stark and skeletal; other times, a coin crusted with rust. You never know if the next detail will spark thoughts of civilization or the pull of material things.

This movie is a feast—it’s a retelling of a real disaster, a portrait of eternal love, a snapshot of the early 20th century’s industrial boom where old and new values clashed across classes, and a projection of the feminine spirit’s ideals, opening windows to different worlds. So, after watching, the title “Time is Like Aged Wine” came to mind. The layering of years and emotions ferments time into a sweet liquor, wafting through the night air with the scent of oak and algae.

The film begins with a lengthy depiction of the wreckage salvage, revealing early on that only the heroine survives—a choice that defies today’s fast-paced, hook-laden, suspense-driven storytelling logic.

Twenty minutes in, the heroine emerges in a soft halo of light, stepping from an ivory-white car. Wearing a deep purple wide-brimmed hat, she’s helped by a chauffeur and ascends the gangway with elegance—an opulent entrance. This contrasts sharply with Jack, who, in a dockside bar, wins his ticket with a poker hand, dashing to the ship’s stern at the last second and squeezing into a cramped third-class cabin. It’s the first layer of contrast: their vastly different statuses. The second layer lies in their words. Rose, boarding, says dully, “This is a slave ship.” Jack, backed by lively Scottish dance tunes, grins, “Good news—we’re off to America to become millionaires!”

Picasso, Degas, Freud

In the first-class palace suite, a maid unpacks Rose’s many suitcases. Flash back to the opening, where elderly Rose arrives by helicopter on the salvage ship, still towing a dozen bags—even her own fish tank. Decades later, she’s kept her own world intact, a woman who, in today’s terms, still has a vibrant soul. Among her paintings is Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, inspired by Iberian sculptures and African masks—distorted bodies and misplaced features, women selling themselves. She holds it up, staring as if into a mirror.

Next, Degas’s Dancers on Stage: a ballerina mid-leap, arms outstretched, watched by another dancer and a man from the wings. She places this in her bedroom—a space where defenses drop, an amplifier for the heart’s secret whispers. The painting in the living room speaks of unchangeable captivity; the one here might be her spirit’s self-rescue.

Then her fiancé calls the Degas “cheap,” and in the next shot locks the “Heart of the Ocean” in a safe. Their desires are clear: Rose yearns for the “moon”, he for “sixpence”. This seemingly perfect match is a tight candy shell, a damp sugar tower—beautiful until you feel it crumbling inside.

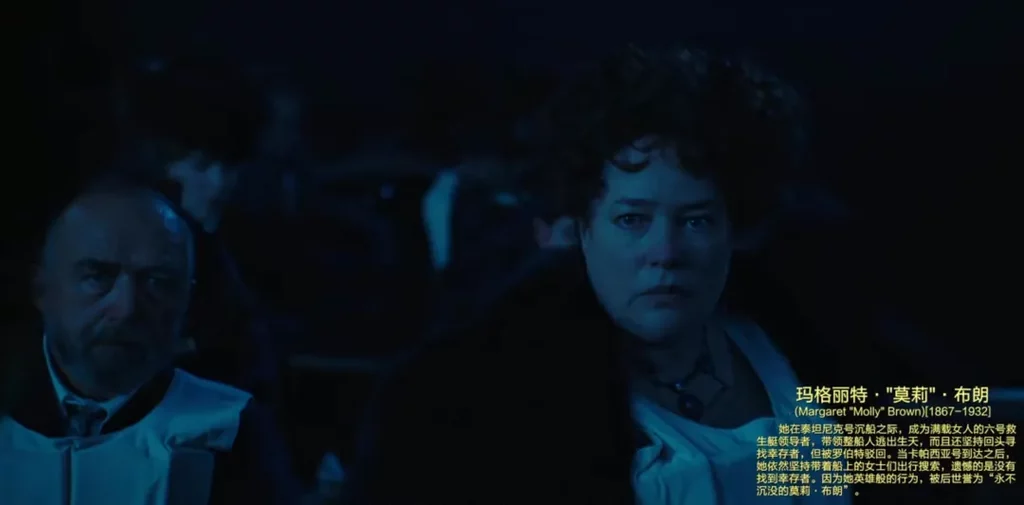

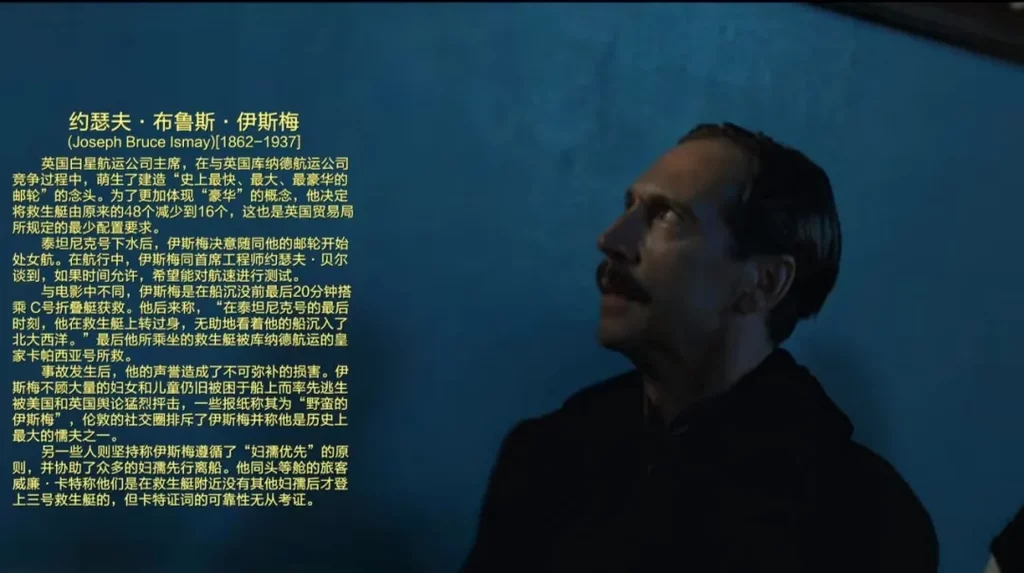

Those who get the joke are Mrs. Brown and Andrews; those who don’t are Ismay, the capitalist, and her sycophantic fiancé. Ismay even asks, “Who’s he? Is he a passenger?”

The Three Camps of First Class

The contrast between these camps continues throughout the film, shaping the characters not through exposition but through their every word and gesture.

Andrews, the ship’s designer, gives up his lifeboat vest, staring at an oil painting as he meets death calmly.

Her fiancé went further, posing as the father of a lone little girl to scramble onto a lifeboat, fulfilling their prophecy: “As you wish, we’ll be remembered by history.”

These are the two threads tracing the opening personas and final acts of each camp’s representatives. I don’t want to define human nature in absolute terms of black or white, good or evil, but this perspective aligns well with the concept of “the beginning of human nature.” Emotions, appearances, and life itself all have an expiration date, yet the essence of human nature at its origin is something that transcends civilization and class, laid bare like an untamed wilderness. This will become even more evident later when discussing the collective fate of people in a shipwreck, forming a tableau of human nature.

I place Rose’s mother in a third-party camp. From the very beginning of the film, her cold disdain for her daughter’s fiancé reveals the arrogance of “old money” toward a “new money” upstart businessman. However, upon discovering Rose’s close relationship with Jack, she can only tell her daughter, “Your father left us nothing but a legacy of bad debts hidden by a good name. That name is the only card we have to play. It is a fine match with Hockley. It will ensure our survival! Why are you being so selfish? We’re women. Our choices are never easy.” She is a woman caught between societal expectations and personal desires. Unlike her daughter, she lacks the courage to break free from convention, instead numbing herself to the sharp edges of reality. Those who defy the current, we call brave; those who choose security, we deem pragmatic. Yet security often comes with a sense of numbness. In the end, as the ship sinks and she sits safely in a lifeboat, watching her daughter go down with the wreck, does she remain silent because she has placed her own survival above all else?

The Sinking: Order Within Each Person’s Chaos

As the ship sank, first-class women and children boarded lifeboats first, while those in steerage were locked behind iron bars. A man pleaded, “You can’t keep us locked in here like animals. The ship’s bloody sinking!” It recalls the book Blindness: “If we cannot live entirely like human beings, at least let us do everything in our power not to live entirely like animals”

Before disaster struck, all was chaos; to speak of order in the face of death is a fool’s dream. Yet these thousands of faces—aren’t they each a reflection of inner order, the most instinctive choices?

A wife, learning her husband wouldn’t join her, refused the lifeboat three times, staying with him: “We have been together for 40 years, and where you go, I go.” A band played amid the sinking; as members parted, a violinist stayed to play alone. Hearing his notes, the other three turned back, joining him to finish their final piece. The fiancé schemed trades to the end. A telegraph operator sent SOS signals until the last. A gentleman, rejecting a life vest, dressed in finery—“I’ll leave as a gentleman”—sipping brandy, smoking a cigar. A priest, forgoing the boat, led passengers in the Rosary. A man draped a shawl, posing as a woman to board. Humanity isn’t black or white—these 2,000 portraits weave a tapestry of society, a record across time, the truest notes and masks.

Rose: A Toast to Her Own Eyes

As the soaring strains of My Heart Will Go On begin, we finally turn to the film’s lovers. Their first glance comes when Jack, sketching on the third-class deck, catches sight of Rose at the first-class railing. Bathed in golden twilight, Kate Winslet glows like a Venus from Botticelli’s brush.

To Jack, she was radiant, untouchable, and high above. But Rose, weary of the endless, hollow galas, returned to her room, tearing off the necklace, hairpins, and corset that bound her, and fled the opulent first-class cabin for the deck. Jack saved her from leaping into the sea, urging her to ride horseback like a man, chew tobacco like a man, teaching her to spit—to do the things she’d longed for but etiquette forbade.

In the first-class cabin, she was shackled by profit and prestige, trembling under her family’s rules. Yet in the steam-filled boiler room, she ran with abandon, the thick mist cloaking the lens and her sight—only to unveil her rawest desires clearer than ever before. Jack, like a mirror glinting in the summer afternoon, reflected the ideals in Rose’s heart, making them shimmer with brilliance.

Some say, “This is a tale of a rich girl falling for a poor boy—Rose boldly chasing ideals and love, a woman in love often like a moth to flame, abandoning fame, status, and wealth for plain, true love.” I partly agree, but rewatching it this time brought fresh insight. Rose is indeed the bravest in this romance, shedding so much, defying the mainstream, twice refusing a lifeboat amid disaster. She’s a fluttering, burning moth, yet in the end, it’s Jack who dives into the flame, giving his life. Sacrifice can be a pitfall in relationships, but in pure, authentic love, it’s a trifle.

These two spirited, confident souls—what we’d now call “a sense of worthiness”—shine bright. Jack never let their vast gap in status or society’s chasm breed insecurity or shame, never saw himself unworthy of the dazzling Rose, nor viewed poverty as an unspeakable affliction. Instead, at the aristocratic dinner, he moved with ease—like a Gatsby a decade hence—unmasking the hollow clamor of the glamorous crowd, stealing the spotlight. In that moment, I could only think: living true matters far more than living “right.”

Rose, too, strikes me as a commanding, rational heroine. After surviving such a catastrophe, saved by Jack’s death, she didn’t let “survivor’s guilt” or trauma dim her remaining years. Perhaps she felt fragile after the wreck, mourned with regret, or dreamed of him with wistful ache. But in her long life ahead, she rode horses astride like he’d urged, living vibrantly in the light he’d sparked within her.

She’d openly recount a love etched deep in her bones, recalling the sultry sketch Jack drew, cherishing a man she’d never forget. For them, meeting in youth was a marvel to last a lifetime—like that final sunset they watched from the ship’s bow, boundless between sky and sea, forever illuminating their lives.

The Heart as a Zen Chamber

The film begins with a salvage team wielding precise instruments, dredging the priceless “Heart of the Ocean” from the deep, and ends with elderly Rose, frail and trembling, casting that “Heart of the Ocean” back into the sea from the ship’s bow. “I’ve thought about it my whole life,” she says. “I came here to put it back where it belongs.” Even in her direst moments, she never traded this gem for material gain—hers was a treasure beyond gold: a human heart.

Yesterday, the green of the hills hadn’t fully unfurled; a brisk spring breeze swept my mind clear and cloudless. My master gifted me four words: “Guard your true heart.” I thought of the “Heart of the Ocean”—isn’t the heart an ocean too? At times, pursuit stirs its spies—desire and pleasure surge, stirring tides, or others unwittingly tag it with worth and judgment, urging us to explain or uphold outer ties for the sake of decorum. Yet the cherished instinct within always pierces through our own and others’ facades. In stillness, perhaps we hear the heart’s drumbeat, a slumbering childhood, the world’s underside. In the zen chamber of the heart, a wisp of incense rises, drifting toward its longing.

Time is like aged wine. Its sharp blade carves foreheads, eyes, and flesh, yet pours forth a draught that makes us weep, sing, wake, and reel—a taste of the human world. Perhaps in ten years, I’ll view this film anew, but every moment is the finest.

好运财运大旺

翻译 Translate

No wonder Captain didn’t review NEZHA 2

Turned out it was Mama turn to do it

翻译 Translate

How about doing movie night together in HongKong in one of HongKong theater ?

翻译 Translate

Did you make notes while you were watching it?

翻译 Translate

How many times you fast forward and rewind this movie while you were watching it, Captain?

翻译 Translate

拜读完了两个语言的版本哈哈哈

翻译 Translate

교수님 추천으로 영화 봤었어요. 졸업하고 상하이 여행갔을때 (철선)이라고 번역된 포스터 본 기억이 나네요. 보스의 영화에 대한 견해가 새롭네요.

翻译 Translate

哇!英文版!!工作人员可以配上语音吗?我们就可以跟读了!

翻译 Translate

This is an age gap !!! 🤣🤣🤣

翻译 Translate

I watched it when I’m in university

翻译 Translate

So much exhausted.

翻译 Translate

Or if, on joyful wing cleaving the sky,

sun, moon, and stars forgot, upward I fly,

still all my song shall be,

nearer, my God, to thee;

nearer, my God, to thee, nearer to thee!

翻译 Translate

Then, with my waking thoughts bright with thy praise,

out of my stony griefs Bethel I’ll raise;

so by my woes to be

翻译 Translate

There let the way appear, steps unto heaven;

all that thou sendest me, in mercy given;

angels to beckon me

翻译 Translate

Though like the wanderer, the sun gone down,

darkness be over me, my rest a stone;

yet in my dreams I’d be

翻译 Translate

still all my song shall be,

nearer, my God, to thee;

nearer, my God, to thee, nearer to thee!

翻译 Translate

E’en though it be a cross that raiseth me

翻译 Translate

Nearer, my God, to thee, nearer to thee

翻译 Translate

Our captain himself has a stable heart and is calm, very charismatic.

So he can send us great energy.

翻译 Translate

He accepted every life with an open mind, respected their diversity and understood their choices.

翻译 Translate